This article is the first in a three-part series examining the Starbucks union’s quest to win a contract with the coffee chain.

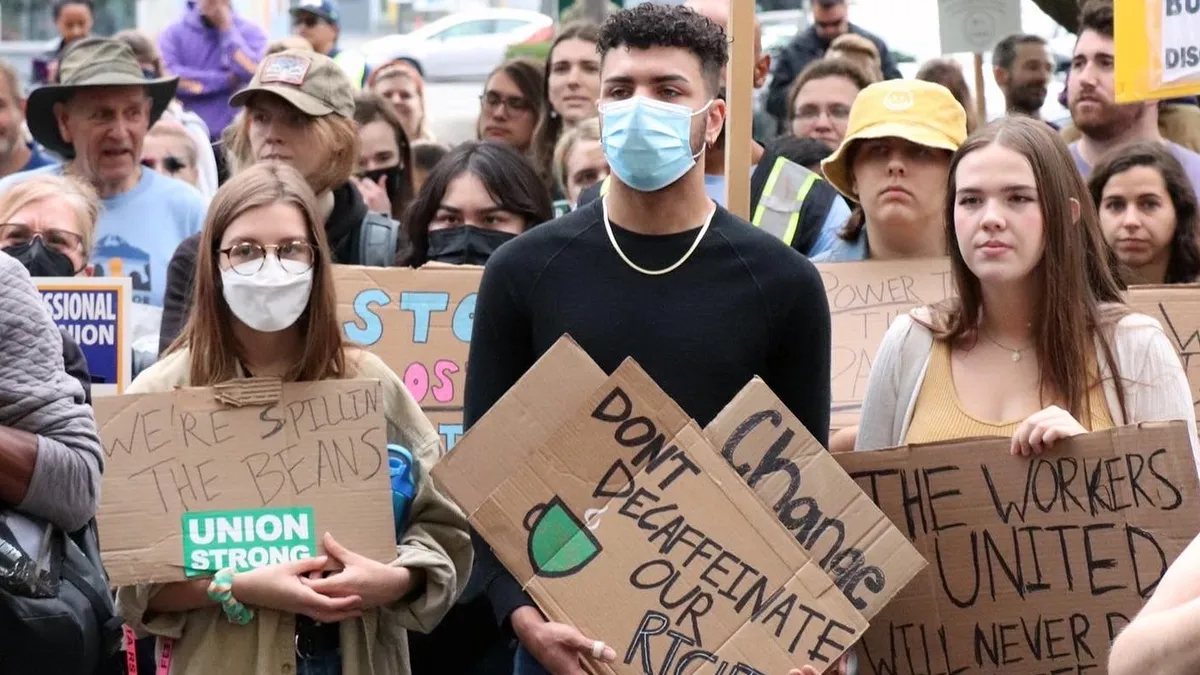

This week marks one year since ballots went out in the first Starbucks union election. Since then, the upstart campaign that started at just a handful of stores has become a powerful national drive, with Starbucks Workers United winning the majority of elections for which it has filed. SBWU now represents about 6,500 workers at over 250 cafes, stoking a sprawling, nationwide battle with the coffee chain.

This string of election victories signals the kind of progress labor leaders once thought to be almost impossible. But election wins don’t guarantee a contract that improves working conditions, which is what many Starbucks baristas are rallying for. It can also take years of collective bargaining to reach an agreement, if the parties reach one at all.

Time isn’t on the union’s side. Just as workers can vote to be represented by a union, they can also vote to cease representation, as outlined under the National Labor Relations Act. Decertification elections can start one year after a union has been certified, or in SBWU’s case, on Dec. 17. That means the union has less than two months to bargain before anti-union workers could begin decertification campaigns in some shops.

The union’s electoral momentum may have already begun to erode, with election filings reaching a low of 8 in August, before rebounding slightly to 12 in September and 12 in October. At the peak of its organizing momentum in March, SBWU filed 71 petitions for elections according to NLRB data.

Unions, experts say, tend to be strongest at the beginning of campaigns. Employer action, turnover and the stress of a campaign can all degrade worker solidarity.

“The day [union supporters] file… with the NLRB, their momentum is at the absolute highest, because from then on, the employer is going to give information [that dissuades workers],” Sid Lewis, an employer-side labor lawyer and union consultant, said. “A lot of employees are going to change their minds.”

The bargaining table is set, and the stakes are high for both corporate and unionized workers. Two meaningful questions remain: Can Starbucks Workers United win a contract? And what strategies could pull it off?

Bargaining is bogged down by accusations of bad-faith negotiations

Bargaining for a first contract, according to labor law experts, follows a fairly set process: the union requests information, the company releases some, and then both sides formulate proposals and agree to meet. Bargaining usually begins with an exchange of non-economic proposals — such as “just cause” termination clauses or sensitivity and non-discrimination training — before proceeding to economic proposals, such as wage and benefits changes.

"Nothing requires an employer to say yes to anything at any time,” Lewis said. Lewis doesn’t represent Starbucks, but spoke to Restaurant Dive about the rules governing bargaining and what employers generally seek in a first contract. The only meaningful requirement during negotiations is that both the union and the company bargain in good faith, he said.

“Good faith bargaining, generally, means bargaining with the intent to reach an agreement, but you're not required to reach an agreement,” Gay Semel, a retired labor lawyer for the Communications Workers of America, said.

This process has already been contentious. In September, Starbucks announced it was willing to begin bargaining at 41 stores in October. As of Oct. 30, the coffee chain is also working to set bargaining dates at 43 additional cafes, Starbucks spokesperson Andrew Trull said.

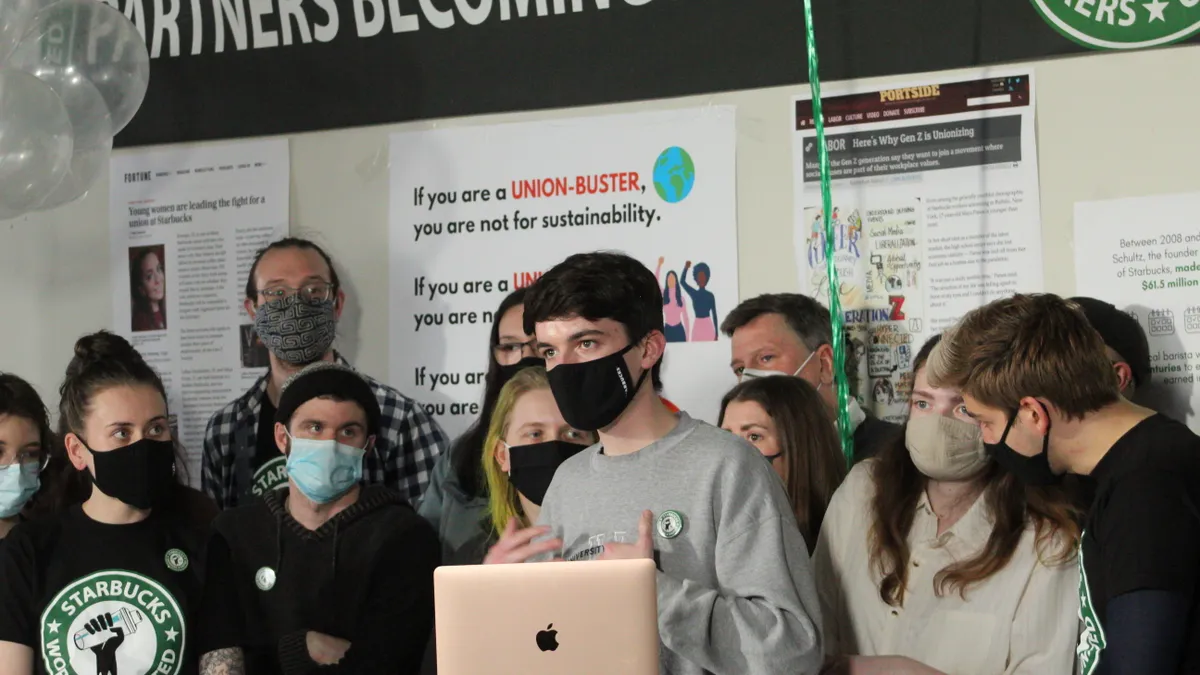

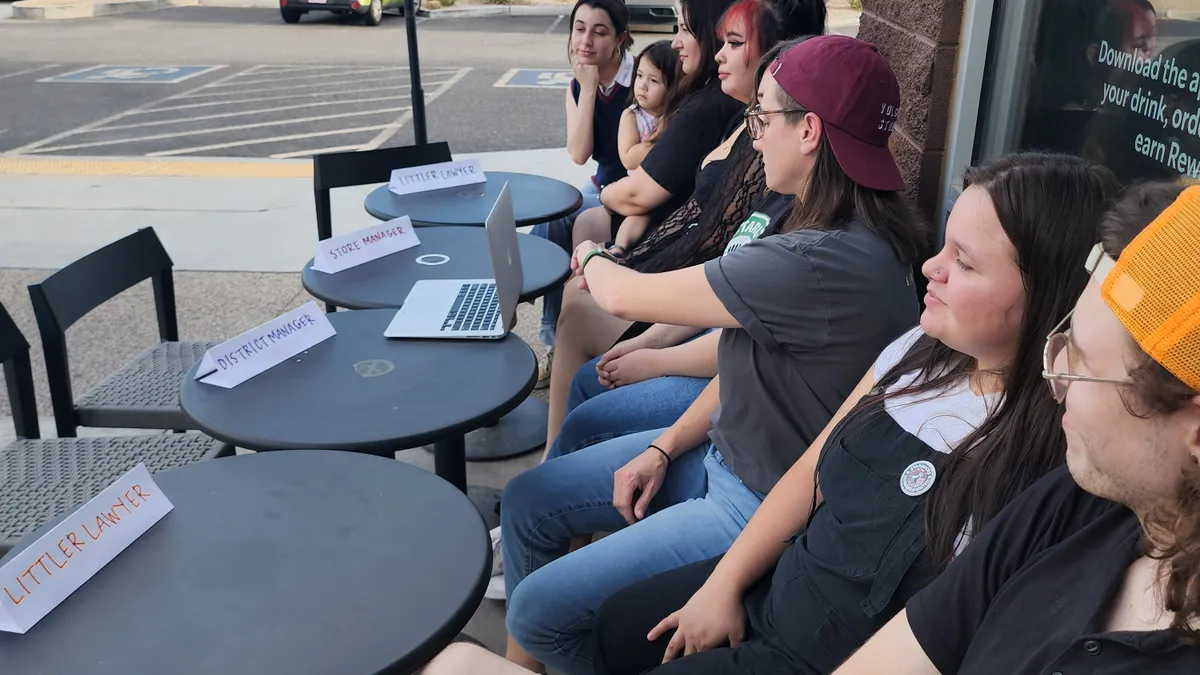

The company and the union agreed to several dozen bargaining sessions beginning on Oct. 24, said Megan Brown, Starbucks barista and SBWU national bargaining committee member. But since then, both Starbucks and the union have accused each other of bargaining in bad faith, NLRB records show.

Starbucks refuses to engage Zoom participants in sessions

Starbucks charged Workers United with bad-faith bargaining because the union included members of its national bargaining committee on Zoom at bargaining meetings around the country. Prior to those meetings, Starbucks asked that bargaining be conducted in-person.

Trull said Starbucks’ bargaining team has walked away from any table where the union was using Zoom to include workers who were not physically present, whether that included workers unable to schedule time off, or members of the union’s national bargaining committee.

The company objects to the use of Zoom, Trull said, “because negotiations that may happen at the bargaining table may warrant discussion of individuals by name and could address sensitive topics.” Starbucks also feels there’s no guarantee that workers on Zoom are who they say they are, and no guarantee they aren’t recording sessions — which is prohibited by the NLRB — via Zoom feeds. Starbucks accused SBWU members of recording bargaining sessions, referencing a TikTok showing Starbucks representatives leaving a bargaining room without any discussion of proposals.

But the union, according to national bargaining committee members, did not agree to terms barring Zoom participation. Bargaining sessions in Buffalo, New York, and Mesa, Arizona, were conducted with Zoom participants this spring, as were some bargaining sessions over store closures. Starbucks said remote bargaining was acceptable in earlier meetings because the company was still responding to COVID-19 as a pandemic.

“Starbucks will get up from the table and walk out as people are speaking,” said Julie Langevin, a Starbucks shift manager and member of the union’s national bargaining committee, who has worked with the company for 17 years. She added that no bargaining session for the national contract has lasted more than a few minutes.

“One of the Starbucks lawyers in Philadelphia went so far as to say ‘you might as well go read [the union’s non-economic proposals] in another room, we are not going to listen to you until you turn the Zoom camera off,’” Langevin said.

The company’s first proposal for large-scale bargaining included a range of dates that left workers insufficient time to request hours off for bargaining, Langevin also claims. Starbucks said it worked with the union afterward to find dates when the workers were able to meet.

SBWU condemns corporate walkouts

The union, on the other hand, filed “failure to bargain” charges against Starbucks because of the dozens of instances where Starbucks representatives have walked out.

The NLRB has little power to intervene in bargaining, which is essentially a private negotiation, Semel said.

“If they [the NLRB] find that one party has been in violation of the good faith obligations, the remedy is to tell them to bargain in good faith,” she said.

Both parties are firm in their positions: the union members want to bargain together, including their peers at other stores by Zoom, while Starbucks refuses to agree to hybrid bargaining.

Jennifer Abruzzo, the general counsel for the NLRB, issued a memo in June 2021 outlining potential remedies for “failure-to-bargain” unfair labor practices her office was considering. That list included a requirement that parties submit bargaining progress reports to the agency, reimbursement of bargaining expenses and the creation of bargaining schedules.

Earlier this year, Abruzzo’s office said the NLRB’s regional offices have obtained some of those remedies in settlements between unions and companies.

Union’s prospects may be undercut by turnover, limited financial power

While the scale of SBWU’s electoral gains are significant, its structural constraints reflect the struggles of most unions.

To put the scale of this campaign into perspective, 837,000 workers in foodservice quit their jobs in August — making monthly foodservice turnover over 125 times larger than the union’s membership. A Starbucks spokesperson, speaking on background for an earlier article, also alleged that turnover was higher at union stores than non-union stores, though he declined to provide specific data.

The power of organized workers comes from their ability to withhold labor by going on strike, Lewis said. But that may only work if the financial cost of a strike really stings.

“There's no special tools,” Semel echoed. “How much they [the union] get depends on how strong they are.”

The NPD group estimates that Starbucks’ average unit volume was about $1.52 million in 2021. Assuming unit volume is comparable between union and non-union stores, units represented by SBWU would generate about $380 million in sales per year, equivalent to about only 1.3% of the company’s total revenue of $29.1 billion in 2021. Even a national strike closing every unionized store would amount to a very minor disruption to Starbucks’ sales.

“There's no special tools. How much they [the union] get depends on how strong they are.”

Gay Semel

Retired labor lawyer, Communications Workers of America

Were such a strike conducted for economic reasons, like pay, rather than a bargaining impasse or unfair labor practice, the company would be able to replace strikers permanently — destroying the union. With less than 3% of company-owned North American Starbucks locations unionized, striking presents a strategic risk, and a protracted campaign may not succeed in an industry with such high turnover.

Still, single-store strikes have worked for SBWU in the past. In one instance in Boston, Starbucks workers said a 64-day work stoppage won them a change in attendance policy, though Starbucks maintains it never enforced the policy. There have been, by the union’s count, dozens of other strikes, most of a limited duration with specific objectives.

Semel did point to examples of comprehensive campaigning where unions were able to impact the broader conditions of an industry, or fight major employers. The Service Employees International Union, Workers United’s parent union, is in the middle of a campaign to overhaul California’s fast food industry through a combination of workplace agitation and political pressure. That drive resulted in the controversial passage of Assembly Bill 257 earlier this year, which would create a council to regulate fast food working conditions in California. SEIU is also conducting a corporate campaign against Chipotle in New York City, using the city’s regulatory bodies to punish the chain for violating labor laws.

Starbucks has finite influence

Though the door will soon be open for anti-union employees to kick off a decertification campaign, it would be illegal for Starbucks to openly organize such a drive, both Semel and Lewis said.

“You can just answer questions without really helping them, you can't really help the process along. It's up to the employee[s] to really do that,” Lewis said.

But employers can, and do, circulate materials telling workers when the one-year post-certification period ends, Semel said. Companies can also share how to contact the NLRB to facilitate decertification elections.

The rules for such elections, Lewis said, are the same as for regular elections: at least 30% of workers in a bargaining unit must petition for it, and a majority of voters must vote for decertification for the union to lose its status as bargaining representative.

The union may also be able to use NLRB charges to prevent some decertification campaigns. In some instances, in bargaining units where a sufficient number of unfair labor practices complaints have been filed by the NLRB regional offices, the board will not allow decertification petitions to proceed, Semel said.

Still, SBWU’s path forward is perilous. The union could fail due to the slow attrition of the labor market and decertification elections, or it could go down in a single decisive strike against the company.

Even if the union wins a first contract with Starbucks, Semel said, that contract may only apply to basic matters, and it could take long cycles of negotiation, confrontation and conciliation to develop more comprehensive terms.

But it’s an uphill battle some workers are determined to fight.

“I don't want to live in a world where I don't get a say in how my life functions and operates. And I've done that for too long,” Langevin said. “I have found a renewed dedication to fighting for people who are being taken advantage of.